My boss told me that my goal in this quarter is to working on Continuous Integration for our current product, and all of a sudden I think there’s a lot of gap between the goal and my current skill. The first thing came into my mind is that: “Ohhh, I am still not quite familiar with Git”. After a short period of panic, I sit down to learn about git. And here’s my note.

If you think you could learn git with manual after you learn how to branch, commit and merge, then you might probably be dispointted. Git is very flexible but it do something in a more novel way, so certain understanding of it’s internal is necessary for mastering it, and would be helpful when you look for help in manual. For example, I hear about so many terms such as “HEAD”, “Index”, “Ref”, “Staging Area”, but I could not tell exactly what is that, and I don’t even know how git works. After some diving, I wrapped something very basic in this post.

Terms

HEAD

The first one is “HEAD”. It could be described as any of following:

- The symbolic name for commit you’re working on top of.

- Always points to the most recent commit of the checkouted branch.

- Is the parent of your next commit.

When you commit, the status of current branch is altered and this change is visible through HEAD.

To Navigate from HEAD, we could use ^ notation and ~ notation

- HEAD^ -> the commit before HEAD

- HEAD~{Number} -> the {Number}th commit before HEAD

If we navigate to a git repo and cat the .git/HEAD file, the content is telling us that we need to look at the file refs/heads/master in the .git directory to find out where HEAD points.

1 | $ cat .git/HEAD |

And the .git/refs/heads/{CURRENT_BRANCH} points to the last commit of this branch.

After we switch the branch, we could see that the HEAD is now pointing to another branch.

1 | $ git checkout hotfix |

Most git commands which make changes to the working tree will start by changing HEAD.

The second term is index.

Index

- Index – where you place files you want committed to the git repository.

- Alias

- Cache

- Directory cache

- Staging area

- Staged files

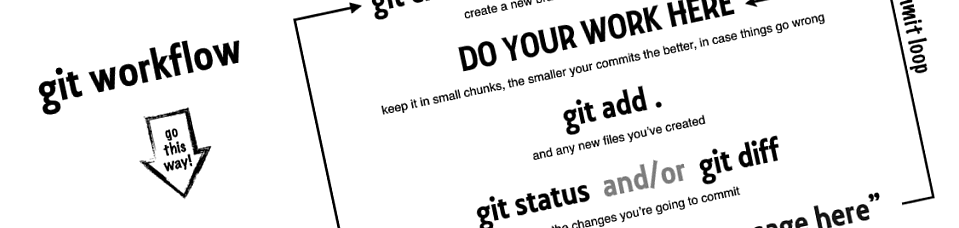

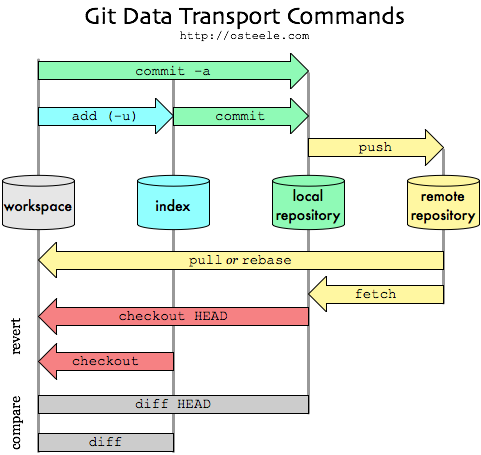

After we git add <file> a file, it’s in the index. See the light blue box in the following workflow chart.

Ref

- Ref is not mysterial, it is just a reference (pointer) to a commit/tag/branch.

1 | $ git show-ref |

We could use git cat-file -p to get the content of a pretty-printed reference.1

2

3

4

5

6

7$ git cat-file -p refs/heads/master

tree 5a20d43b086432fbee9775a1a1f042523733b807

parent 29b9e11cf64b8a1901341be6a20899ec3bd306ca

author wenzhong <wenzhong@example.com> 1413274718 +0800

committer wenzhong <wenzhong@example.com> 1413274718 +0800

remove p13nsingal checking pipeline in bundle

How Git store history?

OK, It’s time to take a look at how git work.

The secret lies on the “.git” directory, and the “objects” sub directory store all objects and history of this repository.

| name | Usage |

|---|---|

| .git/HEAD | file, Point to current branch |

| .git/index | file, store staging area info |

| .git/refs | directory, store pointers points to commit |

| .git/objects | directory, store all data |

For a newly initialized repo, the objects directory looks like this1

2

3

4$ tree .git/objects

.git/objects

├─ info

└─ pack

After I do a simple commit, the objects directory are now with 3 new objects added.

1 | $ echo "test object v1" > README.md |

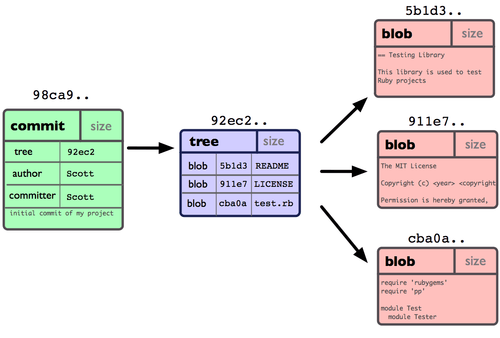

So, what is this? There’s mainly 3 types of objects in git – “Commit”, “Tree” and “Blob”.

- A BLOB is a file under a version

- A TREE is a directory, including blobs and sub-tree (sub-dir) under this dir.

- A COMMIT will point to the repository tree it based on, and also contain commit info (author,message)

cat-file is our friend. Let’s examine the object with it. The “-t” parameters will tell us the type of this objects.

1 | $ git cat-file -t c0baa8366339e7e0d2e8a1f4d2a6b70e38ce9164 |

It’s a commit and contain a tree object “ef0f….”.

1 | $ git cat-file -t ef0f5c785b315ad24cbd5997b67090fc71b7c5ce |

The tree object now contain a blob object.

1 | $ git cat-file -t abb08c95ed3c6e5623f0e5b49bcdff0cbac74d4a |

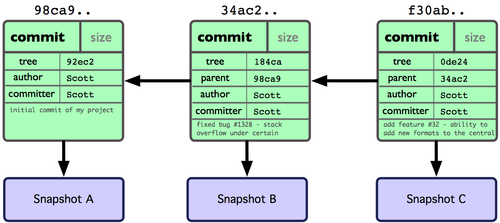

Then, how about multiple commits? how each commit know which commit it based on?

There would be a parent pointer pointing to the last commit in each commit object.

Now we should have a basic understanding about how git store our history in the .git/objects.

SHA1 digest

- In Git, objects are named / located via its SHA1-digest.

- SHA1 will generate a 160 bit Byte array

- Object abb08c95ed3c6e5623f0e5b49bcdff0cbac74d4a will be sent to the “ab” directory

1 | .git/objects |

What about SHA1 collision

really really really damn unlikely

– Linus

- But if it happens

- no new object is created.

- commit will ends up pointing to old object.

- could be noticed in

git pullorgit cloneor something might relavant to a tree diff - Fix it by adding minor comment

Here’s an example to give you an idea of what it would take to get a SHA-1 collision. If all 6.5 billion humans on Earth were programming, and every second, each one was producing code that was the equivalent of the entire Linux kernel history (1 million Git objects) and pushing it into one enormous Git repository, it would take 5 years until that repository contained enough objects to have a 50% probability of a single SHA-1 object collision. A higher probability exists that every member of your programming team will be attacked and killed by wolves in unrelated incidents on the same night.

Branching

Branch is cheap

- Questions: What does “branching is cheap” mean in Git?

- Answer: Switching branch in Git is simply moving a lightweight movable pointer to one of existing commits.

Create a branch

When run

git branch {name_of_branch}, a few things happen:- A reference is created to the local branch at: .git/refs/heads/{name_of_branch}. point to the commit of current HEAD points to.

- A reference is created to the local branch at: .git/refs/heads/{name_of_branch}. point to the commit of current HEAD points to.

Switching branch is moving HEAD

Merge

From the branch you currently on, use git merge $FROM_BRANCH to merge changes from $FROM_BRANCH.

1 | $ git branch master |

- Another useful option to figure out what state your branches are in is to filter output from

git branch -vto branches that you have or have not yet merged into the branch you’re currently on. The useful –merged and –no-merged options have been available in Git since version 1.5.6 for this purpose. To see which branches are already merged into the branch you’re on, you can rungit branch --merged

1 | $ git branch --merged |

Because I have merged “try_branch” branch, so I see it now. How about this?

1 | $ git checkout -b hotfix |

No branch is un-merged? Why?

The reason is that we just create a branch and no commit on it, so both the HEAD pointer of master branch and hotfix branch are pointing to the same commit 3729056.

1 | $ git branch -v |

now do something on hotfix branch. And rerun the git branch --no-merged

1 | $ git commit -a -m "apply a hotfix" |

Good, now merge the new commit.1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23$ git merge hotfix

Auto-merging README.md

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in README.md

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

$ vim README.md

$ git add README.md

$ git commit -m "merge hotfix"

[master cc87eec] merge hotfix

$ git log --graph --pretty='%h %s'

* cc87eec merge hotfix

|\

| * 75828cc apply another hotfix

| * f7963a5 apply a hotfix

* | ec00aea apply change on master

|/

* 3729056 merge the try_branch branch

|\

| * 802e6ea first commit on try_branch

* | 4292dd0 add example of pretty print in git log

* | 986eda3 add useful git log options usage

|/

* 9b7dcc9 add some further change

* 6e2494b init commit

Remote Branches

It’s important to remember when you’re doing above that these branches are completely local. When you’re branching and merging, everything is being done only in your Git repository — no server communication is happening.

This used to cause a few headache. Let’s add a remote repo (in this case, bitbucket.org. Of course we could switch it to github).

`git remote add origin ssh://git@bitbucket.org/wenzhong/git_learning.git`

And push all refs to this origin after creating an empty project on bitbucket.

1 | $ git push -u origin --all |

The -u parameters here is telling git that, for every branch that is up to date or successfully pushed, add upstream (tracking) reference, so they could be used by argument-less git-pull command

And let’s pretend there’re other collaborators who clone this code and push some update. I check out this code to another location (how about call my first local repo “repo1” and this new local repo “repo2”?)in my laptop. And add some changes.

1 | $ git commit -a -m "some changes" |

Now, there’re 2 different states. 1 state from remote repo (bitbucket.org) and it has been updated by repo2. 1 state from repo1, which is identical with the initial state on remote repo before repo2 push his changes. repo1 know nothing about repo2, now do some change on “repo1” and try to push my work to the remote repo.

Synchronize work

Now I run git fetch origin from repo1.

This command looks up which server origin is (in this case, it’s bitbucket.org), fetches any data from it that I don’t yet have, and updates my local database, moving my origin/master pointer to its new, more up-to-date position.

At this time, there’re still two branch for repo1 – origin/master, local/master. They are not the same. origin/master include changes from repo2. local/mastera include changes from repo1, they are not pushed yet. That means we get a reference to origin’s master branch locally.

But now I want to share my work, push it up to the remote. my local branches aren’t automatically synchronized to the remotes I write to – I have to explicitly push the branch.

Now use git push origin master. Note that master is the branch name of my local branch. You can also use git push origin master:new_master to create a new_master branch on remote “origin”. Next time, when repo2 fetches from server, they will get a references to where the server’s version of new_master is under the remote branch origin/new_master.

$ git push origin master:new_master

...

To ssh://git@bitbucket.org/wenzhong/git_learning.git

* [new branch] master -> new_master

Now, repo2 can fetch this new branch by git fetch origin

$ git fetch origin

From bitbucket.org:wenzhong/git_learning

* [new branch] new_master -> origin/new_master

It’s important to note that when you do a fetch that brings down new remote branches, you don’t automatically have local, editable copies of them. In other words, in this case, you don’t have a new new_master branch — you only have an origin/new_master pointer that you can’t modify.

$ git checkout -b new_master origin/new_master

Branch new_master set up to track remote branch new_master from origin.

Switched to a new branch 'new_master'

So far so good. But wait, what happen if I push the repo1/master to origin/master? I assume there would be conflicts.

1 | $ git push origin |

Follow it’s hint and run git pull origin master

Clean your change before Merging

1 | $ git pull origin master |

Git require that our repo should be clean before merging remote changes, so local repo will not corrupted.

See man git-merge

Warning: Running git merge with uncommitted changes is discouraged:

while possible, it leaves you in a state that is hard to back out of

in the case of a conflict.

So, let’s commit our current change (or do a git stash) and try to merge changes from origin/master brought by repo2.1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9$ git commit -m "add syncing remote & local repo"

[master 205e4ce] add syncing remote & local repo

1 file changed, 43 insertions(+)

$ git pull origin master

rom ssh://bitbucket.org/wenzhong/git_learning

* branch master -> FETCH_HEAD

Auto-merging README.md

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in README.md

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

That’s expected, remember that in repo2, we move the tip section to the bottom. (Yes, if you check out commit 986eda3, tips are on top of this README file. and repo2 put it to the bottom at commit 93965e6). So resolve conflicts. and git commit -a -m "merge changes from repo2 and apply my fix"

1 | $ git push origin master |

That’s it.

To summarize, in repo1, we:

- Fetch change from origin/master (latest updated by repo2)

- try to automatically merge our local change (but could not)

- merge it locally

- push to origin/master

Deleting Remote Branches

Now I think the branch “new_branch” have finished its duty, and I want to delete it from the remote server. I will use git push origin :new_branch. A way to remember this command is by recalling the git push [remotename] [local- branch]:[remotebranch] syntax that we went over a bit earlier. If you leave off the [localbranch] portion, then you’re basically saying, “Take nothing on my side and make it be [remotebranch].”

1 | $ git push origin :new_master |

Rebasing

In Git, there are two main ways to integrate changes from one branch into another: the merge and the rebase.

- With the

rebasecommand, we can take all the changes that were committed on one branch and replay them on another one. It works by:- going to the common ancestor of the two branches (the one you’re on and the one you’re rebasing onto),

- getting the diff introduced by each commit of the branch you’re on,

- saving those diffs to temporary files,

- resetting the current branch to the same commit as the branch you are rebasing onto,

- and finally applying each change in turn.

Cherry-pick

A more fancy way to merge changes is the git cherry-pick.

git cherry-pick - Apply the changes introduced by some existing commits

A typical use case is that you could pick some commits from a dev branch to master branch (not all of them).

Another use case I could think of is that when tracking a bug, you might add debug info, commit and trigger CI to reproduce problem, and apply fix commit. using cherry-pick then you could only apply don’t have to remove the debug code in your apply fix commit.

Tagging

- Branches are easy to move around and often refer to different commits as work is completed on them.

Branches are easily mutated, often temporary, and always changing.

If that’s the case, you may be wondering if there’s a way to permanently mark historical points in your project’s history.

- For things like major releases and big merges

git-tag - Create, list, delete or verify a tag object signed with GPG by modifying tag reference in .git/refs/tags/

Describe how far way from you and the tag?

- you could use

git describeto Show the most recent tag that is reachable from a commit - output of

git describewill be<tag>_<numCommits>_g<hash>, Where tag is the closest ancestor tag in history, numCommits is how many commits away that tag is, andis the hash of the commit being described.

Stash

Think about

- working on a new feature modifying files in the working directory and/or index

- and you find out you need to fix a bug on a different branch.

- You can’t just switch / create a different branch because it will lose all your work.

git stash

- Saves your working directory and index to a safe place

- Using

git stash popto restores your working directory and index to the most recent commit

Of course, you could commit your current change, move HEAD to HEAD^, then create a branch. But sometime your current change is not complete as a commit. You don’t want dirty commit added to your repo. git stash give you a clearer way to do this

Hooks

- Some action pre/post each “git action” could be taken by git hooks

- e.g. pre-commit script would be called before commit, here we run a simple ‘run_test.py’ to run test before actually commit something

1 |

|

Tips and Tricks

Inspect commits

There are many options can be used in git log. Some are extremely useful:

- git log –graph

- git log –stat

- git log –since=”2013-10-01” –before=”2014-03-01” –author=fwz

1 | git log --pretty="%h - %ad - %an - %s" |

git show– reports the changes introduced by the most recent commit:

Auto completion

- Git comes with a nice auto-completion script for Bash User.

- Get the latest git-completion.sh from Github

- Put it in your HOME directory and

- Put

source ~/git-completion.shto source it when you login. - This also works with options, which is probably more useful.

1

2$ git log --s<tab>

--shortstat --since= --src-prefix= --stat --summary

if you use zsh, you can get more surprises.

For instance, if you’re running a git log command and can’t remember one of the options, you can start typing it and press Tab to see what matches:

That’s a pretty nice trick and may save you some time and documentation reading.

use D3 as an example.

Aliases

Git doesn’t infer your command if you type it in partially. If you don’t want to type the entire text of each of the Git commands, you can easily set up an alias for each command using git config. Note: the global settings

git config global is under ~/.gitconfig. Here’s my simple aliases.

1 | [user] |

Diff

git diff can be used to list differences between working tree and index, or between index and commit, or between working tree and commit

working tree : your working directory.

index file(stage): Files in the git index are files(after git add) that git would commit to the git repository if you used the git commit command. This is a brigde between working tree and commit

commit: the last stage. after commit, all changes will checked in git repo.

1 | git diff : show the differences between working tree and index file |

Diff Cont.

git diff usually list lots of changes to stdout. If you want to use less as the default pager, below is one solution.

For current project

1 | git config core.pager 'less -r' |

For all projects

1 | git config --global core.pager 'less -r' |

Clone

If you just want to clone one branch from github, what you have to do:

1 | git remote add -t $BRANCH -f origin $REMOTE_REPO |

If you jsut want to clone specific commits(say latest commit), what you have to do:

1 | git clone --depth=1 $REMOTE_REPO |

List deleted/Add files

If you want to know when and which commit delete a file,

1 | git log --diff-filter=D --summary |

If you want to know when and which commit add a file,

1 | git log --diff-filter=A --summary |

search string from all versions in git repos

If you want to get a piece of code, variable, function, file in the repo, but you can not find it.

Maybe it has been deleted for long time. How can I know when and who delete it?

1 | git rev-list --all|( |